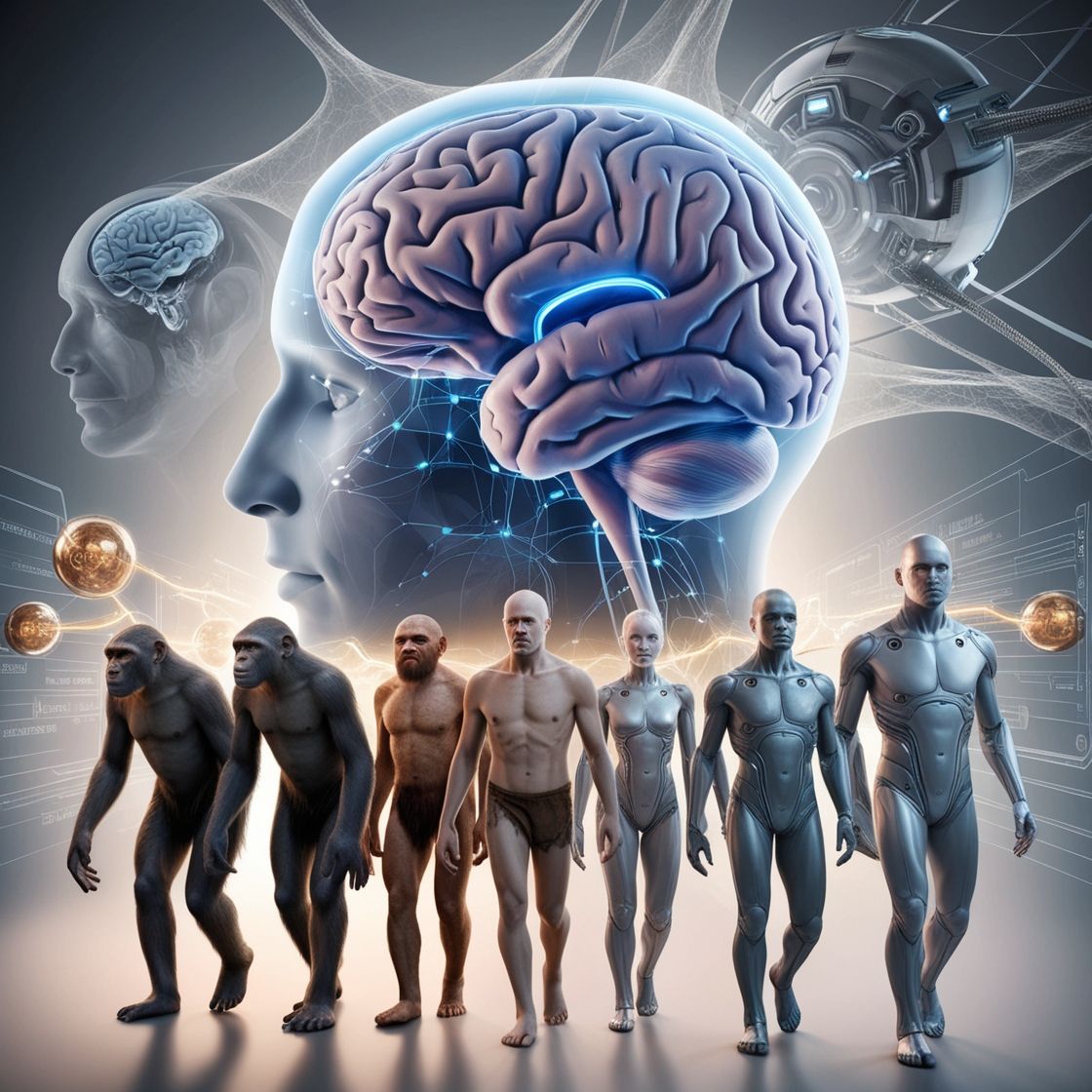

Human civilization has undergone extraordinary transformations, evolving from primitive beings in the Stone Age to the technologically advanced species we are today. As Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution explains, natural selection has played a crucial role in this process. Over time, advantageous traits—like intelligence, cooperation, and adaptability—enabled Homo sapiens to dominate the Earth. However, even as the most intellectually advanced species, we remain entangled in complex conflicts, largely stemming from our psychology and the way our brains function.

Darwin’s insights in On the Origin of Species laid the foundation for understanding biological evolution. But as we’ve progressed, so too has our need to comprehend more abstract elements of our existence—our societies, consciousness, and mental frameworks. Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind examines how these biological foundations gave rise to complex societal structures, enabling us to cooperate on vast scales, create civilizations, and dominate the planet. Yet, Harari also notes that the cognitive revolution, which allowed humans to create shared fictions like money, religion, and empires, has also led to division, inequality, and conflict.

The Evolutionary Paradox: Intelligence and Conflict

Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene furthers Darwin’s ideas by focusing on how genes drive evolution. Dawkins introduced the concept of memes—units of cultural transmission that evolve similarly to genes. Human behaviors, ideas, and even conflicts can be seen as "memes" that propagate across generations. While our intelligence has equipped us with the ability to innovate and build, it has also made us uniquely susceptible to internal conflict. Our ability to cooperate on large scales (Harari’s cognitive revolution) is counterbalanced by tribalism—where we form in-groups and out-groups based on race, religion, and nationality. This is an echo of our evolutionary past when early humans formed small, tight-knit communities for survival. Today, these behaviors persist, often leading to war, discrimination, and social unrest.

Human Psychology: Why We Struggle to Understand One Another

Much of human conflict arises from our brain's inherent complexity and its propensity for irrationality. Daniel Kahneman’s work in behavioral psychology, particularly his landmark book Thinking, Fast and Slow, reveals that human thought operates in two systems: System 1, which is fast, automatic, and driven by intuition; and System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and logical. Though we like to think of ourselves as rational beings, much of our decision-making is dominated by System 1, which is prone to biases and errors.

One such bias is the negativity bias, where humans are wired to pay more attention to negative experiences than positive ones. This bias, rooted in our evolutionary past, is why stress, anxiety, and conflict often seem more overwhelming than they should be. As neuroscientists explain, our brains have evolved to prioritize threats because, for our ancestors, survival depended on recognizing dangers. Unfortunately, in today’s world, where physical threats are less immediate, this bias can distort our perceptions of other humans and lead to unnecessary conflict.

The Dark Matter of the Human Mind

The brain’s complexity is comparable to the universe itself, which is predominantly made up of dark matter and dark energy—forces that are invisible yet essential for holding everything together. In a similar fashion, the human mind harbors unseen forces—emotions, biases, and unconscious drives—that shape our thoughts and behaviors in ways we cannot always control.

Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate argues against the idea that humans are born as blank slates, purely shaped by society. Instead, he asserts that much of our behavior is rooted in biology, inherited through evolutionary processes. This challenges the belief that humans can be entirely rational or purely shaped by environment. We carry the weight of our evolutionary past—our primal instincts for survival, reproduction, and dominance—into the modern world. This explains why, even in our advanced societies, we struggle with issues like war, inequality, and environmental destruction.

The Threat of Self-Destruction: The Power of Technology

In Homo Deus, Harari explores the future of humanity, arguing that we are entering a new phase of evolution—one driven by technology. With advancements in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and nanotechnology, we are beginning to transcend our biological limitations. But with this power comes great risk. Harari warns of the potential for self-destruction, as the technologies that enable our dominance could also lead to our downfall.

Nuclear weapons, climate change, and artificial intelligence all pose existential threats, and the power to control these forces lies in human hands. However, as Harari and Pinker both note, our brain’s evolutionary wiring—its proclivity for tribalism and short-term thinking—makes it difficult to manage long-term threats. This creates a paradox: the very intellect that allowed humans to dominate the Earth also presents the risk of self-annihilation.

The Computer and the Brain: Parallels in Processing

In recent decades, computers have emerged as a fascinating parallel to the human brain. Both are powerful processors of information, yet they operate in fundamentally different ways. The brain processes information via neurons, transmitting electrochemical signals, while computers rely on binary code (0s and 1s). Despite these conceptual similarities, their methods and capabilities differ significantly.

Brain vs. Computers: Processing Power

Human Brain: The brain contains around 86 billion neurons, forming trillions of synaptic connections. It processes information in parallel, handling millions of signals at once, which enables real-time perception, decision-making, and learning.

Modern Computers: Initially, computers used serial processing, handling tasks one at a time. However, modern systems equipped with GPUs and multi-core processors now perform parallel processing, handling thousands of tasks at once. Nevertheless, their parallelism remains limited compared to the brain.

Power and Speed: Brain vs. Computers

Processing Speed: Processing Speed: As of 2024, the Frontier supercomputer is the fastest in the world, with a speed of 1.194 exaFLOPS, surpassing the previous record held by Fugaku at 442 petaFLOPS. Despite this, the human brain's estimated processing capacity of 1 exaFLOP—though not directly comparable to FLOPs—suggests that the brain remains competitive in complex, real-time decision-making, whereas supercomputers excel in raw computational tasks.

Power Efficiency: The human brain is remarkably efficient, consuming only 20 watts, compared to the 30 megawatts required by supercomputers. This stark contrast highlights the brain’s superior energy efficiency.

Memory and Learning: Neural Networks vs. the Brain

Human Brain: The brain’s memory capacity is estimated to be around 2.5 petabytes. However, it’s not just about storage—its true strength lies in its ability to learn, adapt, and generalize knowledge from experiences. The brain processes information efficiently with minimal input.

Machine Learning: Computers attempt to replicate this through neural networks in AI. Although AI has made significant strides in tasks like pattern recognition and games, it still relies heavily on large datasets and computational power. The debate continues over whether human flexibility and creativity remain unmatched, but the brain is more efficient in learning from fewer examples.

Quantum Computing: A New Paradigm

Quantum computers, which use qubits and principles like superposition, represent a new era of computing. Quantum systems excel at specialized tasks like cryptography and complex simulations. However, they remain in the early stages of development and are far from replicating the brain’s general processing capabilities.

Human Cognition and the Laws of Physics

At the core of our inability to manage global crises is a disconnect between our cognitive limitations and the objective realities of the universe. Scientific principles—such as the laws of thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, and physics—are immutable truths that govern the universe. No amount of human ingenuity can change these laws, and yet, as a species, we often act irrationally in the face of these truths.

For instance, the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy (disorder) in a system will always increase over time, can be seen as a metaphor for human societies. Despite our attempts to create order—through governments, economies, and institutions—chaos often prevails. This may be due, in part, to our evolutionary predisposition toward conflict and self-interest, which undermines efforts at cooperation and stability.

Are We Really the Smartest Species?

Given all of this, we must ask ourselves: Are we truly the smartest species on Earth? On one hand, our intelligence has allowed us to create art, philosophy, science, and technology—achievements unparalleled by any other species. On the other hand, our inability to manage our own destructive impulses, biases, and conflicts raises the question of whether we are truly wise.

In conclusion, the human journey from Darwin’s evolutionary principles to Harari’s future visions reflects both the brilliance and tragedy of our species. We are capable of extraordinary innovation and profound understanding of the universe, but we are also burdened by the very traits that enabled our success. To move forward, we must reconcile our evolutionary past with the realities of the present and future. Only then can we truly consider ourselves not just intelligent, but wise.

References:

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species (1859) – Foundational work on evolution and natural selection.

- Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (1976) – Introduced the idea of memes and explored genetic evolution.

- Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens (2011) & Homo Deus (2015) – Provided a historical and futuristic analysis of human evolution.

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) – Explained cognitive biases and human decision-making.

- Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate (2002) – Challenged the notion that humans are purely shaped by environment.